The ECB Grants Debt Relief To All Eurozone Nations Except Greece

Paul De Grawe proporciona una información muy relevante sobre el momento europeo:

As part of its new policy of ‘quantitative easing’ (QE), the ECB has

been buying government bonds of the Eurozone countries since March 2015.

Since the start of this new policy, the ECB has bought about €645

billion in government bonds. And it has announced that it will continue

to do so, at an accelerated monthly rate, until at least March 2017

(Draghi and Constâncio 2015). By then, it will have bought an estimated

€1,500 billion of government bonds. The ECB’s intention is to pump money

in the economy. In so doing, it hopes to lift the Eurozone economy out

of stagnation.

I have no problems with this. On the contrary, I have been an

advocate of such a policy (De Grauwe and Ji 2015). What I do have

problems with is the fact that Greece is excluded from this QE

programme. The ECB does not buy Greek government bonds. As a result, the

ECB excludes Greece from the debt relief that it grants to the other

countries of the Eurozone.

How is this possible? When the ECB buys government bonds from a

Eurozone country, it is as if these bonds cease to exist. Although the

bonds remain on the balance sheet of the ECB (in fact, most of these are

recorded on the balance sheets of the national central banks), they

have no economic significance anymore. Each national treasury will pay

interest on these bonds, but the central banks will refund these

interest payments at the end of the year to the same national

treasuries. This means that as long as the government bonds remain on

the balance sheets of the national central banks, the national

governments do not pay interest anymore on the part of its debt held on

the books of the central bank. All these governments enjoy debt relief.

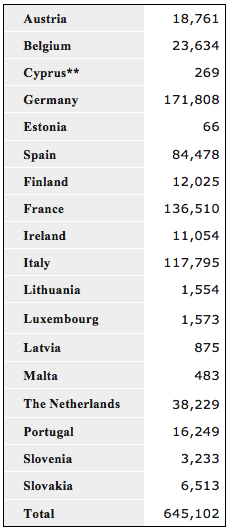

How large is the debt relief enjoyed by the governments of the

Eurozone? Table 1 gives the answer. It shows the cumulative purchases of

government bonds by the ECB since March 2015 until the end of April

2016. As long as these bonds are held on the balance sheets of the ECB

or the national central banks, governments do not have to pay interest

on these bonds. The ECB has announced that when these bonds come to

maturity, it will buy an equivalent amount of bonds in the secondary

market. We observe that the total debt relief granted by the ECB until

now (April 2016) to the Eurozone countries amounts to €645 billion. We

also note the absence of Greece and the fact that the greatest adversary

of debt relief for Greece, Germany, enjoys the largest debt relief from

the ECB.

The announcement of the ECB that it will continue its QE programme

until at least March 2017 and that it will accelerate its monthly

purchases (from €60 billion to €80 billion a month) implies that the

debt relief that will have been granted in March 2017 will have more

than doubled compared to the figures in Table 1. For many countries,

this will amount to debt relief of more than 10% of GDP.

Table 1 Cumulative purchases of government bonds (end of April 2016)

(million euros)

(million euros)

link al artículo completo

link al artículo de de Jorg Bibow: El caso para el abandono del euro por Alemania#Gexit

#Gexit, the departure of the strong, would be less disruptive for the

Eurozone as a whole. Germany could declare next Sunday that it

re-introduces the deutschmark converting all domestic euro contracts and

prices at a 1:1 rate. (Perhaps the Dutch and Austrians might consider

going along with it, but I leave that possibility aside here.) On Monday

morning the Bundesbank would stand by and cheer the new deutschmark

surge on the exchanges. It would follow the advice of Deutsche Bank and raise German interest rates to make sure savers get their well-deserved rewards.

The German government would proudly announce to its citizens that

they will no longer have to bail out any lazy Europeans but will from

now on enjoy the real fruits of their hard-won übercompetitiveness. And

so all Germans would live happily ever after. Tranquilized by their

stability-oriented ideology they would ignore any discomfort coming

along with the chosen deflationary adjustment; just as they have ignored

the agonies experienced elsewhere in the Eurozone since 2009. And they

would be troubled even less by any surges in indebtedness (and resulting

bankruptcies), private and public, coming along with such a

deflationary adjustment; just as they saw no reason to concern

themselves with these kind of side effects elsewhere in the Eurozone

since 2009 either.

Essentially, the current Eurozone has Germany’s euro partners serving

as the economic wasteland that is keeping the euro low so that German

exports have it easier globally. By contrast, the new Eurozone (ex

Germany) would see its external competitiveness restored instantly,

especially vis-à-vis Germany itself; while, internally, any remaining

competitiveness imbalances would be minor compared to a status quo that

includes Germany. Unshackled from German idiosyncrasies in all matters

of macroeconomics, the Eurozone would follow through with my Euro

Treasury plan and henceforth smartly invest in their joint future – a

future of prosperity rather than impoverishment. Unhindered by German

pressures and supported by constructive rather than destructive fiscal

policy the ECB would continue its current course and re-establish price

stability in a couple of years. If they preferred to return to their

national currencies, that would be the other avenue to climb out of

their euro trap. I personally think that, if the Euro Treasury were

established, the members of the Eurozone (ex Germany) would be better

off with the euro. But that is their choice to make.

Meanwhile, Europe is far too important to be left to the Germans.

Jörg Bibow