The Collapsing Euro and Its Implications - LewRockwell LewRockwell.com: The euro system and its currency are descending into crisis. Comprised of the ECB and the National Central Banks, the system is over its head in balance sheet debt, and it is far from clear how that can be resolved. Normally, a central bank is easy to recapitalise. But in the case of the euro system, when the lead institution and all its shareholders need to be recapitalised all at the same time the challenge could be impossible. And then there’s all the imbalances in the TARGET2 system to resolve as well before national legislatures can sign it all off. … Continue reading →

Fiddling while Rome burns…

Now that Eurozone CPI is rising at 8.6% and Germany’s producer prices are up 33.6%, either interest rates must rise smartly or the euro crashes. Our headline chart of the euro/dollar rate at the top of this article refers to the market’s reaction so far.

Bonds in the ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme have accumulated as shown in the chart below, split out into the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP), Corporate Sector Purchase Programme (CSPP), Asset-backed Securities Purchase Programme (ABSPP) and the Third Covered Bond Purchase Programme (CBPP3). In June, they totalled €3,265,172 million.

Given that government stock is 65% of the total, the rest being generally higher yielding corporate bonds, a conservative estimate is that if the portfolio has an average maturity of ten years the mark-to-market loss from a year ago is already in the region of €750bn. This is almost seven times the combined euro system balance sheet equity and reserves of €109.272bn. And as yields rise further, euro system losses of double that are easy to imagine.

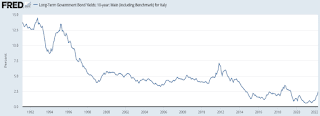

The market rate for Italy’s 10-year government bond was a yield of 12.4% when the Maastricht treaty setting the conditions for entry into monetary union came into effect in 1992. Germany’s equivalent benchmark yielded 8.3% for a differential of 4.1%. Today the German benchmark yields 1.35% and the Italian 3.37%, a difference of 2.2%. Not only has the gap converged, but by the end of 2021 the quantity of Italian government debt had increased to over 150% of GDP.

Table A shows the relationship between the Eurozone G-SIBs’ balance sheet totals, their balance sheet equity, and market capitalisations to illustrate the fragility of the Eurozone’s global systemically important banks (G-SIBs).

Much of the devil is to be found in those non-performing loans. It has become routine for national regulators to deem them performing so that they can act as collateral for loans from the national central bank. When they then become lost in the TARGET2 settlement system they are forgotten, and miraculously the commercial bank appears solvent again. But TARGET2 becomes riddled with those bad debts and imbalances arise as the next chart from the Euro Crisis Monitor shows. In theory, these imbalances should not arise, and before the Lehman crisis it was generally true

At end-May, Germany’s Bundesbank was “owed” €1,160bn.

At the same time, the greatest debtors, Italy, Spain, Greece, and Portugal have combined TARGET2 debts of €1,255bn. But the most rapid deterioration for its size is in Greece’s negative balance, more than tripling from €25.7bn at end-2019 to €106bn in April. Spain’s deficit is also increasing at a worrying pace, up from €392.4bn to €505bn, and Italy’s from €439.4bn to €597bn.

If one national central bank runs a Target2 deficit with the other central banks, it is because it has loaned money to its commercial banks to cover payments, instead of progressing them through the settlement system. These loans to commercial banks appear as an asset on the national central bank’s balance sheet, which is offset by a liability to the ECB’s Eurosystem through TARGET2 — hence the PIGS’ deficits. In effect, central banks running deficits are providing their commercial banks with extra liquidity. This is mostly done through repurchase agreements, more of which anon. The fact that commercial banks in the PIGS require this liquidity is a red flag.

Germany’s equity ownership in the ECB is 21.44% of its capital.[i] If TARGET2 collapsed, the Bundesbank would lose over a trillion euros owed to it by the others and the ECB itself, and pay up to €387bn of the net losses, based on current imbalances. It would wipe out the Bundesbank’s own balance sheet many times over.

In Italy’s case, the very high level of non-performing loans (NPLs) peaked at 17.1% in September 2015 but by March this year had been miraculously reduced to 4%.[ii] Given the incentives for the regulator to deflect the non-performing loan problem from the domestic economy into the Eurosystem, it would be a miracle if the reduction in NPLs is entirely genuine. And with all the covid-19 lockdowns, Italian NPLs will be soaring again along with Italian banking exposure to Russia and Ukraine. There’s no sign of this being reflected in national banking statistics, so it must be concealed somewhere.

Officially, there is no problem, because the ECB and all the national central bank TARGET2 positions net out to zero, and the mutual accounting between the central banks in the system keeps it that way. To its architects, a systemic failure of TARGET2 was inconceivable. But because some national central banks are now accustomed to using TARGET2 as a source of funding for their own insolvent banking systems, the Ukraine crisis and the rising interest rate environment attributed to producer price and consumer inflation threaten to increase imbalances even further, potentially bringing the euro-settlement system crashing down.

The euro system member with the greatest problem is Germany’s Bundesbank, now owed well over a trillion euros through TARGET2. The risk of losses is set to accelerate rapidly because of repeated rounds of Covid lockdowns in the PIGS and now with the Ukraine situation. Under Jens Weidmann (who has since resigned) the Bundesbank was right to be very concerned.[iii]

This is a direct quote from the highly respected Professor Sinn’s paper on the subject:

“… the Target issue hit political headlines when the new President of the German Bundesbank, Jens Weidmann, voiced his concerns over the Bundesbank’s target claims in a letter to ECB president Mario Draghi. In the letter Weidmann not only demanded higher credit rating criteria for collateral submitted against refinancing loans, but also called for collateralisation of the Bundesbank’s soaring Target claims. Weidmann wrote his Target letter after several months of silence on the part of the Bundesbank, during which it conducted extensive internal analysis of the Target issue. This letter marked a departure by Weidmann from the Bundesbank’s earlier position that Target balances represent irrelevant balances and a normal by-product of money creation in the European currency system.”[iv]

But the problem remains: as a mechanism that permits the PIGS to shelter nonperforming loans in increasing quantities, the TARGET2 setup has become rotten to the core and off the record is known to be. And now, thanks to the economic impact of the coronavirus followed by Ukraine, sooner rather than later the settlement system is set to fail completely.

Until then, TARGET2 is a devil’s pact which is in no one’s interest to break.

A TARGET2 failure would appear to require the ECB to recapitalise itself and the whole eurozone central banking system.

The ending of TARGET2 is therefore likely to be a complete write-off for the national central banks and will mark the end of the ECB, at least in its current form. And we haven’t even mentioned the immediate impact of rising interest rates, let alone the failure of TARGET2 on the Eurozone’s commercial banks.

Shuffling non-performing loans into central banks is achieved principally through the repo market. Under a repurchase agreement (repo), a bank swaps collateral for cash, a transaction which is reversed later. In this way the central bank ends up with collateral, which has been cleared as “performing” by the local bank regulator, and the commercial bank gets cash and a seemingly clean balance sheet. Any amount of rubbish can be concealed by these means.

The euro repo market is enormous, estimated by the International Capital Markets Association to have been €8.726 trillion outstanding in June 2021. It is far larger than the US dollar equivalent, which at the moment is just over $2 trillion of reverse repos, i.e. the other way with the Fed taking in cash instead of dishing it out. While much of this excess in euro repos is the consequence of negative interest rates, even paying banks to borrow against government bond collateral, it is of such a size as to easily hide bad and doubtful debts within the central bank settlement system.

The ECB has fostered this market, because it creates demand for government debt to be used as colateral, which with minimal and even negative yields would not otherwise be bought. Rising interest rates will collapse this market, withdrawing liquidity from the commercial banks and putting yet more pressure on them to reduce their balance sheets.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the ECB must prevent rising interest rates and bond yields at all costs, not only to preserve the euro system itself, but to prevent a collapse of the entire commercial banking network.

Assuming the status of the euro as a medium of currency and credit is to continue, a different and formulaic system of currency management designed to recapitalise the national central banks and keep the currency moderately scarce throughout the Eurozone would have to be implemented. And because its implementation would have to be instantaneous, it would probably prove to be impossible. Therefore, the euro is extremely unlikely to survive its systemic crisis.

The EU’s future following the ECB’s failure

The failure of TARGET2 would require national central banks to address their own relationships with their commercial banking networks properly. It is beyond our scope to see how this might be done in individual jurisdictions, being more interested in the bigger picture and the prospects for the euro and its successors.

Therefore, it is now a when, rather than an if, the TARGET2 system collapses. Foreign G-SIBs appear to have low exposure to the euro system and its commercial banking network, evidenced during the US’s repo crisis in September 2019, when the sale of Deutsche Bank’s primary dealership to BNP was completed. Consequently, the immediate currency effect is likely to be driven by domestic Eurozone entities, rather than foreign liquidation.

The case for a new mark

It therefore follows that somewhere in the bowls of the Bundesbank there is a Plan B in existance, which at the least will be intended to insulate the Bundesbank from the difficulties faced by other national central banks and the ECB itself in a crisis. This can only be achieved with a new currency, based on the German mark before it was folded into the euro. That way the euro-based Bundesbank can be written off as the Eurosystem collapses, while a mark-based Bundesbank emerges.

The Bundesbank will be acutely aware what pursuing its own interests would mean for the PIGS, and also for France whose eurozone ambitions are entirely political. Interest rates in the replacement currencies for these nations would almost certainly rise sharply, collapsing their bond markets insofar as they still exist, undermining any surviving commercial banks, and destroying national finances. These nations would have no practical alternative but to seek the shelter of a better form of money than the euro to re-establish their bond markets, and with a view to having continuing access to credit. In short, the monetary consensus could eventually move from an overtly inflationary monetary system gamed by the national central banks and their regulators to one based on a sounder form of currency and credit.

For this reason, the mark is unlikely to be offered up as a replacement for the euro.

The obvious solution is for German to adopt a credible gold standard, and to encourage other member states to do the same. Figure 2 shows the official gold reserves of key member states.[vi]

Not only does a successful gold standard require balanced budgets, but a deliberate reduction in overall spending must be maintained for the standard to stick over time. The failure of the Maastricht treaty in this respect illustrates the difficulties of fiscal discipline in the European context.

Politically, it requires a reversal of the European social democratic ideal, risking a political vacuum, threatened to be replaced by various forms of extremism.

International influences

The political and monetary evolution of a post-euro Europe will not be determined solely by endogenous events. There is a similar but less complex crisis evolving in Japan, equally leading to a failing yen mirroring the euro. And both the Fed and the Bank of England are desperately hoping that they won’t be forced to raise interest rates to reflect persistent price inflation. And everywhere that significant financial markets exist, they are under the doleful influence of the bear.

Obviously, the implications of several separate developing crises for each other and the timings involved cannot be predicted beyond guesswork, but there are common threads. The most notable is that the suppression of interest rates and government bond yields by the major central banks has come to an end.

Central banks have maintained their objectives by the inflation of currency and credit, allowing debt creation to balloon and inflate financial asset bubbles. These bubbles have different systemic characteristics. The ECB and Bank of Japan along with a few others imposed negative interest rates while, the Fed and Bank of England have respected the zero bound. With the US economy being more financial in nature and the dollar being the international reserve currency, the dollar’s loss of purchasing power is the primary driver of global commodity and energy prices.

A common linkage between major financial centres is through the G-SIBs. A failure in the eurozone’s banking system will almost certainly undermine that of the US, as well as of the others. History has shown that even a minor bank failure in a distant land can have major consequences worldwide. In this context, it is to be hoped that by exposing the faults in both the TARGET2 system and the eurozone’s commercial banks, a greater understanding of the monetary dangers faced by us all has been achieved. And for citizens in the EU, the regaining of national power from the Brussels bureaucracy is the opportunity for an improvement on the current situation — assuming it is used wisely.

https://www.goldmoney.com/research/the-collapsing-euro-and-its-implications

No comments:

Post a Comment